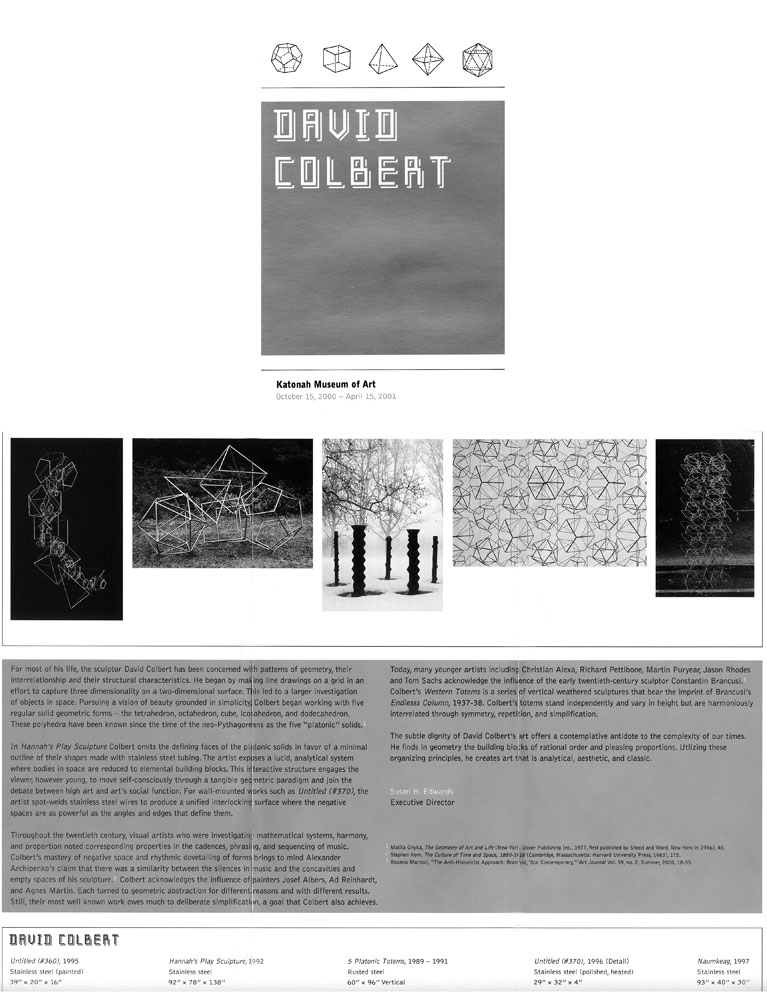

For most of his life, the sculptor David Colbert has been concerned with patterns of geometry, their interrelationship and their structural characteristics. He began by making line drawings on a grid in an effort to capture three dimensionality on a two-dimensional surface. This led to a larger investigation of objects in space. Pursuing a vision of beauty grounded in simplicity, Colbert began working with five regular solid geometric forms – the tetrahedron, octahedron, cube, icosahedron, and dodecahedron. These polyhedra have been known since the time of the neo-Pythagoreans as the five “platonic” solids. (1)

In Hannah’s Play Sculpture Colbert omits the defining faces of the platonic solids in favor of a minimal outline of their shapes made with stainless steel tubing. The artist exposes a lucid, analytical system where bodies in space are reduced to elemental building blocks. This interactive structure engages the viewer, however, to move self-consciously through a tangible geometric paradigm and join the debate between high art and art’s social function. For wall-mounted works such a Untitled (#370), the artist spot-welds stainless steel wires to produce a unified interlocking surface where the negative spaces are as powerful as the angles and edges that define them.

Throughout the twentieth century, visual artists who were investigating mathematical systems, harmony, and proportion noted corresponding properties in the cadences, phrasing, and sequencing of music. Colbert’s mastery of negative space and rhythmic dovetailing of forms brings to mind Alexander Archipenko’s claim that there was a similarity between the silences in music and the concavities and empty spaces of his sculpture.(2) Colbert acknowledges the influence of painters Josef Albers, Ad Reinhardt, and Agnes Martin. Each turned to geometric abstraction for different reasons and with different results. Still, their most well known work owes much to deliberate simplification, a goal that Colbert also achieves.

Today, many younger artists including Christian Alexa, Richart Pettibone, Martin Puryear, Jason Rhodes and Tom Sachs acknowledge the influence of the early twentieth-century sculptor Constantin Brancusi.(3)Colbert’s Western Totems is a series of vertical weathered sculptures that bear the imprint of Brancusi’s Endless Column, 1937-38. Colbert’s totems stand independently and vary in height but are harmoniously interrelated through symmetry, repetition, and simplification.

The subtle dignity of David Colbert’s art offers a contemplative antidote to the complexity of our times. He finds in geometry the building blocks of rational order and pleasing proportions. Utilizing these organizing principles, he creates art that is analytical, aesthetic, and classic.

Susan H. Edwards

Executive Director

1Matila Ghyka, The Geometry of Art and Life (New York:Dover Publishing Inc.,1977, first published by Sheed and Ward, New York in 1946),40.

2 Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1983),175.

3 Roxana Marcoci, “The Anti-Historicist Approach:Brancusi, ‘Our Contimporary,’” Art Journal Vol.59, no.2, Summer, 2000, 18-35.